A few years ago, my husband and I asked an Orthodox woodworker to make coffins for us (sorry, he has since retired). They’re beautiful, with the angelic Trisagion Prayer, “Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal,” lettered all the way around. Whenever I go in the basement, I pass by these coffins.

A few years ago, my husband and I asked an Orthodox woodworker to make coffins for us (sorry, he has since retired). They’re beautiful, with the angelic Trisagion Prayer, “Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal,” lettered all the way around. Whenever I go in the basement, I pass by these coffins.

Sometimes we joke about them. I had my husband take a photo of me sitting in one, and I sent it to our kids with the caption, “Does this make me look fat?”

But the other day the thought suddenly came to me: what will it be like to be shut up inside that coffin? How would it be, to lie with that lid just inches from my face?

It was an upsetting thought. I gave myself a lecture: I’ve been a Christian for almost 50 years, and I certainly should be able to do better than that. It’s not that I have any doubts about Paradise or the Resurrection. No, it was just that first moment of death, that first step into darkness. Suddenly, it was overwhelmingly scary. I said, “Lord, I really really really don’t like that. I really don’t want that to happen.”

![]()

Oddly enough, there is an icon that shows a saint having that same horrified realization.

This is the Desert Father Abba Sisoes of Egypt, looking into the broken tomb of Alexander the Great. The conqueror was once great and powerful, but now he is just rotten bones. These words are lettered on the icon:

<<Sisoes, the great ascetic, stands before the tomb of Alexander, King of the Greeks, who was once covered in glory. Astonished, he mourns the ravages of time and the fleeting course of glory. He tearfully cries out:

“The mere sight of your tomb overcomes me, and I shed tears from the heart, as I ponder this debt which we all must pay. O Death! Who can escape you?”>>

And that’s how I felt, still saying “I really really really…”

It occurred to me that what I’ve got is mostly fear of the unknown. So I decided to look up in Scripture the stories when someone dies, or returns from the dead, and see if it lets you know anything about the afterlife. I came up with six—and a half. We’ll go through them quickly, because after doing this I realized that there’s another fear, and it’s fear of something we do know, something we know all too well. But first we’ll go through the six and a half Scriptures.

Part I – The Unknown

The first one is about the time the Prophet Elisha was walking alon

The first one is about the time the Prophet Elisha was walking alon g with his teacher Elijah, and suddenly “a chariot of fire and horses of fire appeared and separated the two of them, and Elijah went up to heaven in a whirlwind.” (2 Kings 2:11)

g with his teacher Elijah, and suddenly “a chariot of fire and horses of fire appeared and separated the two of them, and Elijah went up to heaven in a whirlwind.” (2 Kings 2:11)

To be honest, I think that’s kind of scary; I don’t even go on roller coasters. But it sure oesn’t sound anything like looking at the underside of a wooden lid. Whatever Elijah was experiencing at that moment, it wasn’t mere endless darkness. It was more like the start of an extraordinary new life.

And eight hundred years later, Elijah shows up again.

This time, he’s standing next to Jesus, with Moses on the other side, and all three of them are ablaze with light (Luke 9:28-36). Centuries after his chariot ride Elijah is still out and about, and apparently none the worse for wear.

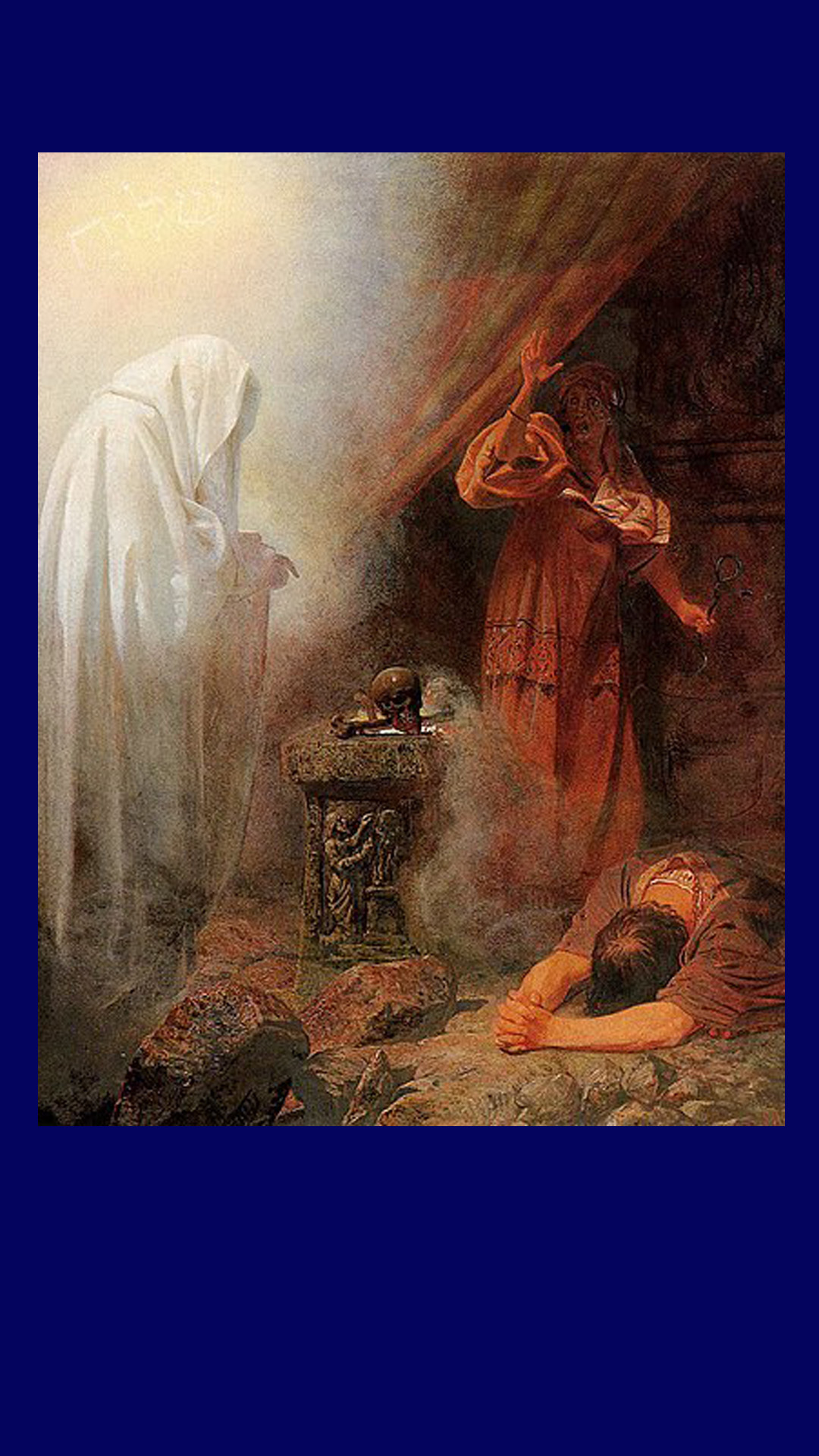

- Second, there’s the time King Saul hired a medium to call the Prophet Samuel back from the dead (1 Samuel 28:3-25).

You might think a dead person would be happy to come back to life. But Samuel was grouchy about it, and said, “Why have you bothered me, raising me up?” / Whatever Samuel was experiencing after death, he liked it better than this earthly life. But he doesn’t tell us anything about it! I wish he’d told us something about what it’s like.

You might think a dead person would be happy to come back to life. But Samuel was grouchy about it, and said, “Why have you bothered me, raising me up?” / Whatever Samuel was experiencing after death, he liked it better than this earthly life. But he doesn’t tell us anything about it! I wish he’d told us something about what it’s like.

Then he hit King Saul with some very bad news.

He said that, because of Saul’s disobedience, God has abandoned him. Tomorrow, Samuel says, “You and your sons will be with me.” When Saul hears this, he falls to the ground.

It occurs to me that this story shows both sides. Saul is having a very natural Sisoes-like reaction to the thought of dying the next day. But Prophet Samuel seems to like his current abode better than this earthly life. He could have said why, you know.

- Third, there’s Jesus’ parable about the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31). When poor Lazarus died, Jesus says, “he was carried away by the angels to Abraham’s bosom.”

Being carried away by angels is just fine with me. And I will point out that no fiery chariots are involved.

Next I was going to say next that “Abraham’s bosom” means they are banqueting in the Roman style, reclining on long couches, and Lazarus can lean back and rest his head on Abraham’s chest.

But that’s not how icons depict it. And I should explain why that matters.

In Orthodoxy, our icons, prayers, and worship change so little, from one time and culture to another, that we can look to them to understand the Orthodox faith. They teach us what Orthodox people have consistently believed, over the centuries and across the continents. They show us where there is consensus.

That’s community memory, and that is a worthy guide. Nobody can change it, because it goes back so far in history. Someone who tried to change things would just demonstrate that he had left the community.

So, when I looked up icons of Abraham and Lazarus, I was surprised to see that they don’t show them reclining at a banquet. Instead they depict Abraham seated with a baby, or many babies, in his arms.

Imagine starting over in Paradise, as a baby! That would be all right, too. Of course we wouldn’t literally be babies, but it shows we would be gently taken care of. That’s a reassuring thought, given all the unknown.

These angels are bringing Abraham babies so fast he doesn’t know where he’s going to put them all.

These angels are bringing Abraham babies so fast he doesn’t know where he’s going to put them all.

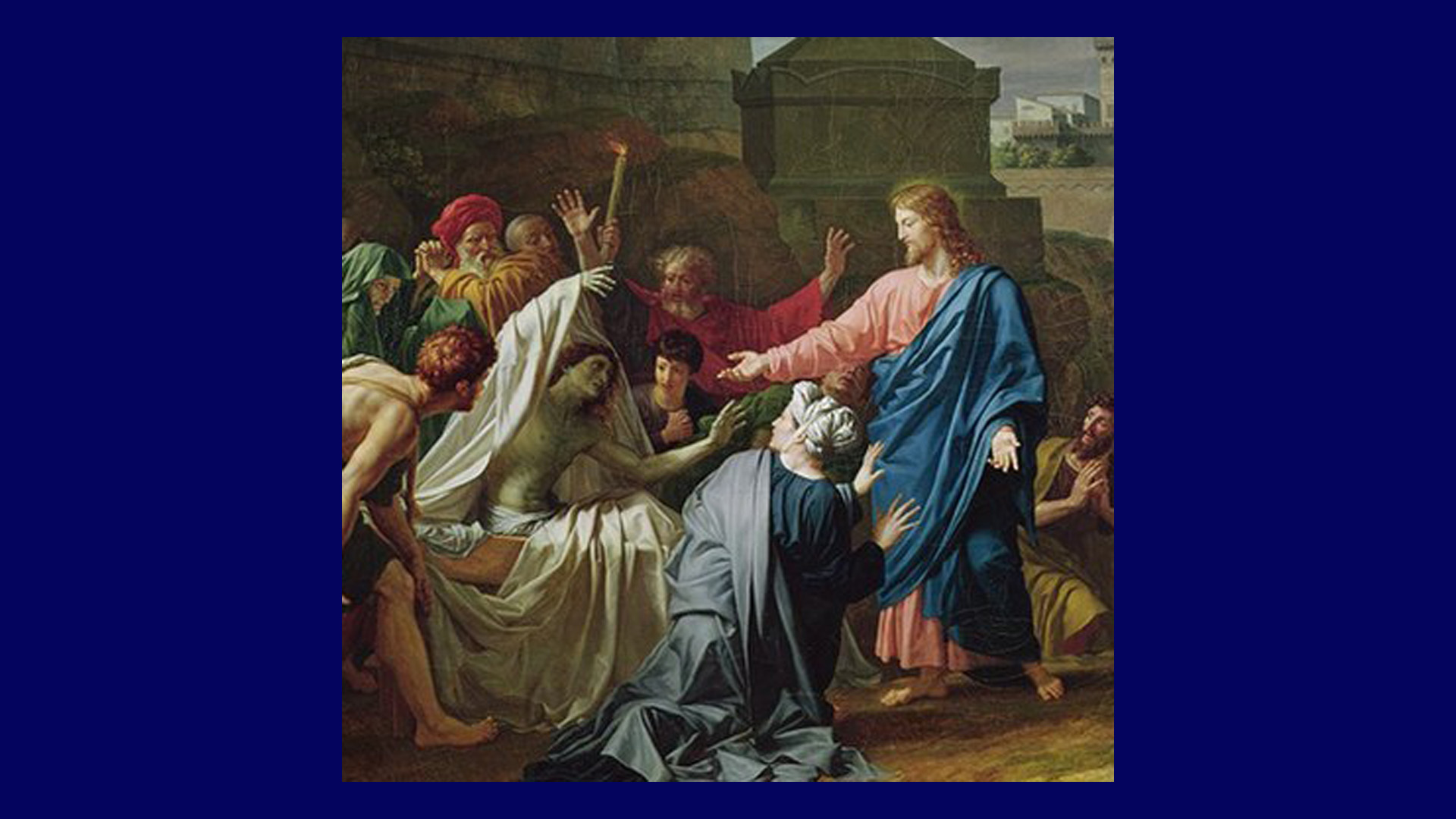

- Fourth, there’s the time Jesus raises the son of the widow of Nain (Luke 7:11-17).

St. Luke says, “When the Lord saw her, he had compassion on her, and told her ‘Don’t cry.’ Then he came up and touched the bier, and those carrying it stood still. He said, ‘Young man, I say to you, arise!’ The dead man sat up, and began to talk.”

He began to talk? What did he say? Did he talk about where he’d been?

Did nobody write that down? Cause that could have been some really useful information.

- Fifth is the other Lazarus, Jesus’s friend, Lazarus of Bethany, whom Jesus raised from the dead (Luke 11:1-44).

Lazarus of Bethany had been in the tomb four days when Jesus arrived. That was plenty of time for his body to start decomposing, and icons usually show people covering their noses.

Lazarus of Bethany had been in the tomb four days when Jesus arrived. That was plenty of time for his body to start decomposing, and icons usually show people covering their noses.

Four days was also plenty of time for Lazarus to look around and size things up. But if he ever told anybody what he saw, it wasn’t recorded.

Whatever it was, it made Lazarus very serious. He lived another 30 years as bishop of Cyprus, and it’s said that he never smiled or joked—except one time. Once Lazarus saw a thief stealing a clay pot, and he smiled and said, “Clay is stealing clay”.

- And sixth is St. Stephen, the first Christian to die for his faith. And he does tell us something he saw, right at the edge of death. He said:

“I see the heavens opened, and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God!” (Acts 7:56).

That reminds me of something I read some years ago, in an account of Christian missionaries who were martyred in the Middle East. I can’t find it now, and maybe it was just hearsay. But the story was that, when the faithful were lined up, kneeling, about to have their heads cut off, you can see in the video that one of the women suddenly looks up in amazement; and you can see her lips forming the name, “Jesus!”

I hope that’s true. But as I said, I can’t find it anywhere.

So that’s six, and here is the half. It’s St. Paul’s vision of being caught up to “the third heaven.”

Now he doesn’t say that this happened one of the times when he was near death; but he does say he went to in Paradise. He describes the experience modestly, in the third person:

<<I know a man in Christ who fourteen years ago was caught up to the third heaven—whether in the body or out of the body I do not know, God knows. And I know that this man was caught up into Paradise—whether in the body or out of the body I do not know, God knows; and he heard things that cannot be told, which man may not utter.>> (2 Corinthians 12:1-5).

Here at last we have someone who has been to Paradise, telling us what it was like—and all he says is that he’s not allowed to say anything. It’s not a big help.

Even if the next life is still unknown, we do know that God is good, and whatever he gives us will be beautiful. There’s a story popular on the Internet about accepting that goodness on trust, even if we can’t picture what it’s like.

The story is about unborn twins who are discussing the possibility of life after birth.

The first twin states that there is no life after birth, because nobody has ever come back. But the second twin thinks that their life in utero might be preparation for another life, where their arms and legs will have a purpose, and where they will see more light. He says that he believes in the existence of a Mother.

That makes the skeptical twin laugh. He says, nobody has ever seen a Mother, so how can one exist?

The thoughtful twin says that, nevertheless, he believes she is all around them. She made them and she loves them. And sometimes, when he is very quiet, he can hear her voice. When life-after-birth begins, he says, they will see her face to face.

St. Paul says, (1 Corinthians 2:9), “Eye has not seen, nor ear heard, nor has it entered into the human heart, what God has prepared for those who love him.”

Part II – The Known.

But even when we have gotten past our fear of the unknown, there’s something else about death, and it’s something we know all too well. It’s the reason Abba Sisoes looks so horrified, as he gazes into Alexander’s tomb. It’s because he is looking at a decaying corpse.

That’s what gives me the creeps. I try to imagine that this comfortable body, this one right here, is going to rot. This dear body that I’m so fond of, that I like to pamper and decorate. St. Paul said, “No one ever hates his own flesh, but nourishes and cherishes it” (Ephesians 5:29). And it’s like he can see me, in the candy aisle.

But one day this oh-so-precious little body will stop, and it will go into that wooden coffin, and that will go down in a deep hole and be covered with dirt. And after that, my body will “return to dust” (Psalm 90:3)—but not without going through many unpleasant stages along the way.

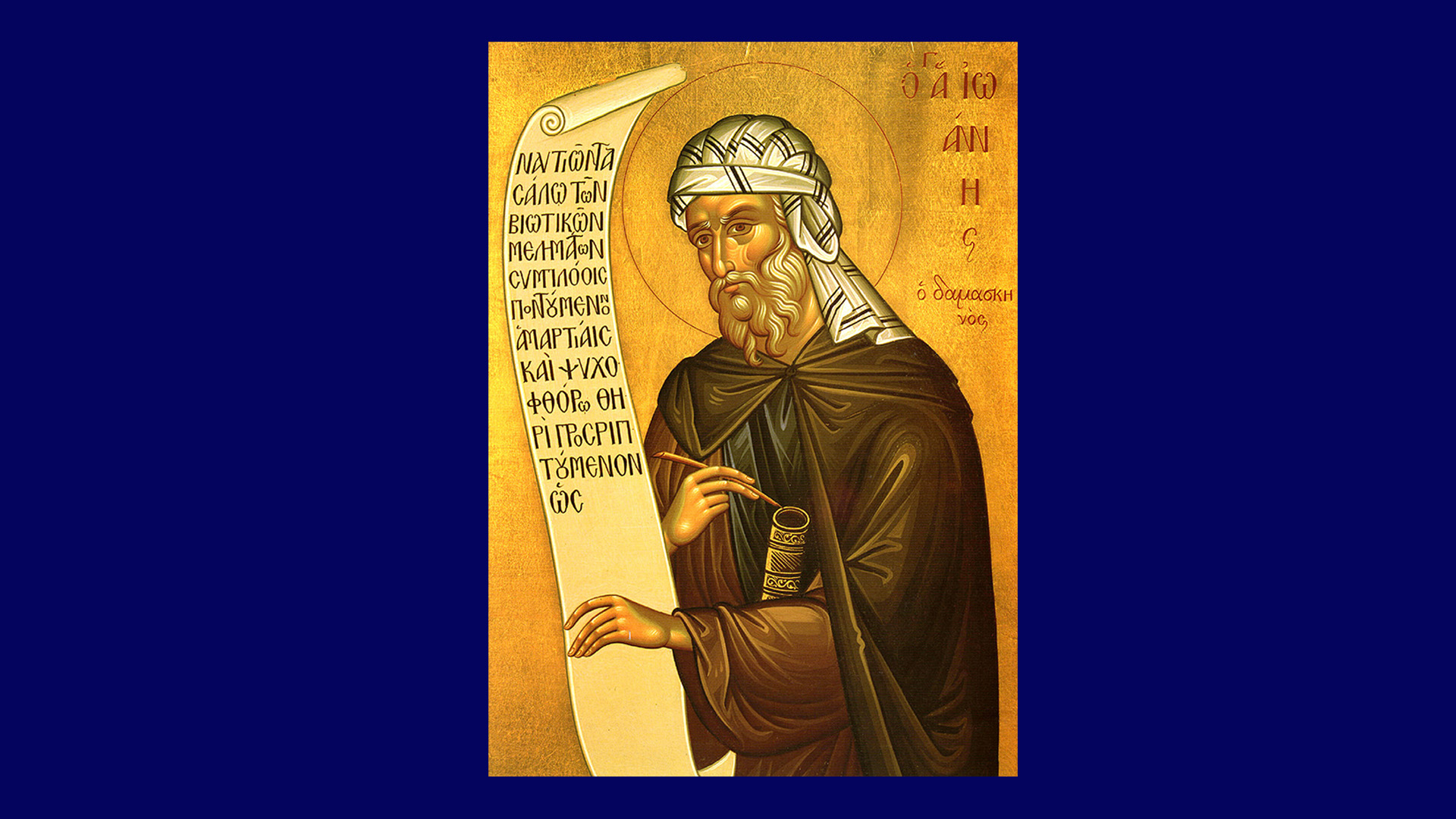

St. John of Damascus (675-749) wrote a hymn that we still sing at Orthodox funerals, and it contains this verse:

<<I weep and lament when I think of death,

and see our beauty,

formed in the image of God,

now lying in the tomb,

shapeless, disfigured, stripped of glory.

How strange this is!

What is this mystery that happens to us?

Why have we been handed over to corruption?

Why have we been wedded to Death?

Yet truly it is by the will of God,

who gives rest to his departed.>>

Now if you’re a Christian writer, at this point it’s customary to look forward, and talk about the Resurrection of the Dead. But I want to look backward. This dear body of mine—where did it come from? What is it made of?

The very engaging writer Bill Bryson wrote a terrific book—I’ve read it more than once—called A Short History of Nearly Everything.

And right on the first page he says,

“It is a slightly arresting notion that if you were to pick yourself apart with tweezers, one atom at a time, you would produce a mound of fine atomic dust, none of which had ever been alive, but all of which had once been you” (p 1-2).

It’s one of the basic laws of physics, the Law of Conservation of Mass. No new matter is ever created; no old matter is ever destroyed. So the atoms that make up your body have been in existence ever since the world began.

In this life we use our allotment of atoms temporarily, to get around. When the time comes, Bryson says, “your atoms will shut you down, silently disassemble, and go off to be other things.”

I have a strong proprietary interest in my particular set of atoms, but I have to recognize that they are merely on loan. And like overdue library books, I will have to return them.

And others before me have already done that. Hard at it is to imagine, it’s their used atoms that I’m cruising around in right now.

Bryson says, “We are so atomically numerous and so vigorously recycled at death, that a significant number of our atoms…probably once belonged to Shakespeare, …Buddha and Genghis Khan and Beethoven.” (He goes on to say, “Apparently… it takes the atoms some decades to be thoroughly redistributed; however much you may wish it, you are not yet one with Elvis.” p 134).

Atoms are God’s Legos. He built the universe with them, and he will go on reusing and rebuilding with them however he likes. Everything I can see around me is a temporary installation. It will all be smashed down and rebuilt, over and over again, until God brings this universe to a close.

So St. Lazarus was right, when he made his little joke. The thief is made of atoms and the clay pot is made of atoms. Clay is stealing clay.

How can you cope with knowing something like that? Something that is terrible, unbearable, and yet you know it’s inevitable? How can you deal with that?

Here’s what I do. If I’m sure I can’t change it, I just accept it.

I recommend that approach. The sooner I can get my thinking lined up with what God is going to do anyway, the better things go.

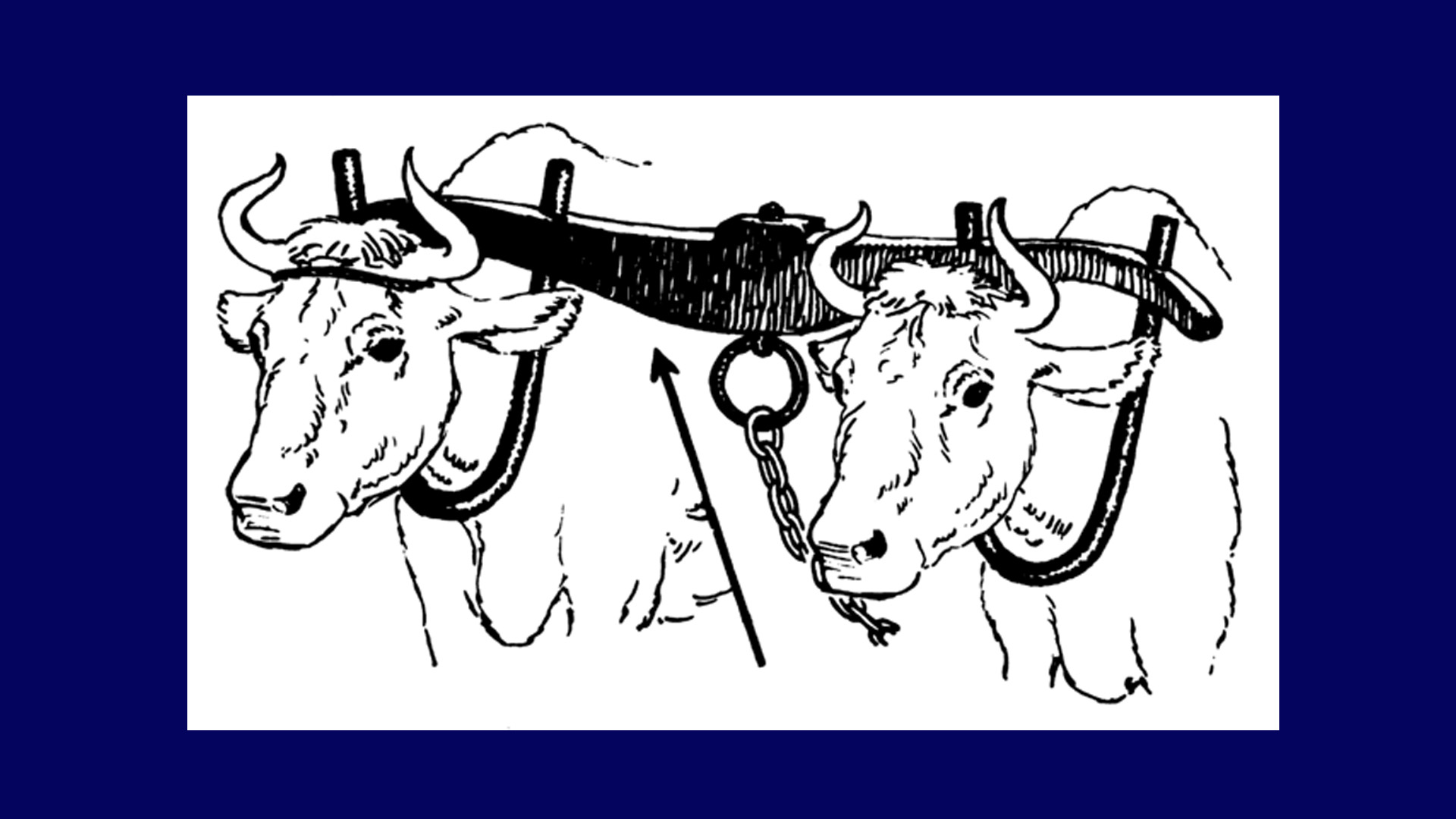

You know how Jesus said “My yoke is easy” (Matthew 11:30)? If you picture two oxen yoked together, you can see right away that things are going to go a lot easier for the smaller ox if he goes the same direction that the bigger ox wants to go. If he tries to follow his own way, it’s just going to make his life more difficult. And he’s going to end up where the bigger ox is going anyway.

You know how Jesus said “My yoke is easy” (Matthew 11:30)? If you picture two oxen yoked together, you can see right away that things are going to go a lot easier for the smaller ox if he goes the same direction that the bigger ox wants to go. If he tries to follow his own way, it’s just going to make his life more difficult. And he’s going to end up where the bigger ox is going anyway.

I have great respect for reality. So, for me, when I see where it is going, I try to adapt to it as quickly as I can.

With this terrible but unavoidable fate before us, it helps me to remember something I saw on a trip to Russia. I was able to go to St. Petersburg and visit the tomb of the beloved Fool-for-Christ, St. Xenia. Her tomb in the middle of an old cemetery, and it’s lovely and well cared-for, and always surrounded by pilgrims.

But a lot of the other tombs in that cemetery are untended, and they are in the process of being retaken by nature. What this place looked like before it became a cemetery, that’s what it is turning into again.

And that seemed to me so fitting. Everywhere, vigorous green life was bursting out, taking over that place of death, and once again turning it wild. Everywhere I looked, green life was swarming over family plots, and throwing a green shroud over names that had once been beloved. Vines were dragging tombstones down, and tree roots were busting them up.

And this seemed to me not only right, but somehow beautiful—even comforting, in a way. Maybe because it demonstrates so clearly the victorious force of life. In that cemetery that force was evident everywhere, powering through every leaf. I looked around and thought, is this cemetery a place of death or of life?

And, to once again get personal, this where we meet our last God-given assignment. When we fall into nature’s final embrace, we are called to return our used atoms to the common warehouse. From there they will go to resume their endless service as mute and never-living bearers of the relentless force of life.

So I guess my fear of death covered a couple of different things. First, fear of the unknown, and I’m attempting to trust God to do something lovely and good, though I can’t know much about it.

The other fear is about bodily disintegration, because the process is so disgusting. But it’s also inevitable, so there’s no use fighting it. We have to return our used atoms, and that’s the way it’s done. Even if I’m not happy about it, I can at least be resigned to going along.

If I imagine a painful death, dying of disease or being martyred, the way I always pictured it is: the pain gets worse and worse and worse and then you DIE.

But that’s not what happens. In reality, the pain gets worse and worse and worse and then it stops hurting. And then you look around and see that you’re in a place you’ve never seen before, and it’s beautiful. You see your beloved Lord Jesus Christ; the Sun of Righteousness is ablaze, and every shadow has fled away.

Back on earth, your familiar atoms are beginning to roll away. But you can just ignore that. Those atoms will have many new and different assignments, and billions of them will turn up in the bodies of people not yet born, not even thought of. But we won’t have anything to do with that. We’ll be in a very different place, filled with the light of Christ.

Let’s return to Abba Sisoes. Eventually it was his turn to die, and his fellow monks wrote a detailed account of what happened.

As Abba Sisoes was dying, his fellow-monks noticed that his face was beginning to glow. Sisoes spoke, and said, “Look, Abba Anthony has come.” St. Anthony the Great, the founder of desert monasticism, had arrived to stand at Sisoes’s deathbed, though Sisoes alone could see him.

Then Sisoes’s face grew brighter, and he said, “Look, the choir of the prophets has come.” The brightness increased yet again, and he said, “Look, the choir of the Apostles has come.”

Then he began speaking quietly with someone. The monks asked who he was talking to, and he said, “The angels have come for my soul, but I am asking them to give me a little more time, to repent.” They said, “Father, you don’t need any more repentance,” but Sisoes replied, “I don’t think I’ve even begun to repent.”

Then his face began to glow even more brightly. He said joyfully, “Look! The Lord has come! And he is saying: ‘Bring me the vessel from the desert!’”

At that there was a flash of lightning, and the room was filled with a wonderful fragrance. And that is how Abba Sisoes surrendered his soul to God.

Thank you for the comforting reflection and pointing the reality we will experience when we pass!

Thank you so much for sharing this piece of writing. It made me remember a book I have recently read called ‘After‘ by Dr Bryce Greyson. Dr Bruce is a scientist and he explores the experience of many people called NDEs or Near Death Experiences. It is a well written book and documents people’s experience of life beyond their own death and then their return to life and how it impacted on their lives moving forward. I would highly recommend it as a book that will encourage you as a Christian not to fear death and it will give you insights that will give you much hope about the life that is yet to come. ‘After’ by Dr Bruce Greyson

I just reread a similar book, “To Hell and Back” (1993) by Maurice Rawlings. It’s very moving and encouraging to hear these stories. Rawlings was a cardiologist and resuscitation expert, and he studied the cases carefully, choosing only the ones where the person was actually resuscitated and had actually died, not just the Near Death Experiences which are usually positive. The true *death* experiences were sometimes positive, sometimes very negative and sobering. It’s a really interesting book.

This is great! Much needed for me to hear. I do have a question about the whole thing regarding my atoms returning and being reused into something else. I understand we return to dust but the way this is presented reminds me of reincarnation. What is the difference?

It’s not our souls that are placed again in a new body–that’s what reincarnation is. Our souls are with the Lord in Paradise. The surprising thing to me, to learn, is that the atoms of our bodies get reused in many different ways, and the atoms we are using now used to be other things, including other people’s bodies. That’s weird, but all right. The thing I wonder about is, how will God resurrect our bodies, if atoms are shared around among so many people? I guess if bones remain, those would be atoms that had not been reused, so they would have a direct link to the soul of the body that’s being resurrected. It’s perplexing all right. But it doesn’t have to do with reincarnation, which is when a particular soul keeps appearing in new bodies. It’s kind of the opposite of that.

Please resend the “FEAR OF DEATH” post

I had a temporary problem with the website, but its back up now.

I have read that the atoms making up our bodies come and go, are added and sloughed off, in the ordinary course of life—such that there is a complete turnover of our bodies’ atoms every several years—all without us having any sense that our bodies have gone away or been replaced. Apparently, it’s not the specific atoms that are key, but some kind of ordering of them, and/or relation to our souls, that makes one’s body one’s body, and makes it subsist even as the component atoms come and go, mostly unnoticed. Pursuing this line of thought further, it seems that getting a full understanding of what I mean when I say, “this is my body” would be an indispensable prerequisite to understand what Jesus meant when He said, “This is My body”.

Very interesting! I don’t know anything about it. I wonder what field or specialty I would look in to grasp it better. Genetics maybe?

Well, while I’ll comment that this datum is suspect due to its NPR provenance, there’s this, for starters:

https://www.npr.org/2007/07/14/11893583/atomic-tune-up-how-the-body-rejuvenates-itself