[March 17, 2020]

This prayer charms all who read it. Though not well-known among Orthodox Christians, it appears in some Protestant hymnals, and in my Episcopalian days I heard it sung at ordinations and on St. Patrick’s feast day (March 17). (Want to sing along? Here’s a Youtube of the piano melody with screenshots of the lyrics.) This hymn stood out, in that context; it wasn’t like other hymns. Different verses were sung to different melodies. It was framed as a series of first-person assertions, rather than as devotional poetry. It seemed, in general other-worldly—even haunting. It was clear that it spoke from another place and time.

This prayer charms all who read it. Though not well-known among Orthodox Christians, it appears in some Protestant hymnals, and in my Episcopalian days I heard it sung at ordinations and on St. Patrick’s feast day (March 17). (Want to sing along? Here’s a Youtube of the piano melody with screenshots of the lyrics.) This hymn stood out, in that context; it wasn’t like other hymns. Different verses were sung to different melodies. It was framed as a series of first-person assertions, rather than as devotional poetry. It seemed, in general other-worldly—even haunting. It was clear that it spoke from another place and time.

The “Breastplate” is popularly ascribed to St. Patrick (5th century), the evangelizer of Ireland, a saint loved by Christians everywhere. In the Old Irish version that has come down to us, the prayer is preceded by an introduction explaining that Patrick composed it when the High King of Ireland, Loegaire, was trying to kill him. Patrick and his clergy, with their young companion Benen, were passing through a forest where the king’s henchmen lay in wait. But the holy men made their way in safety, for the assassins did not see them, but only a line of deer followed by a fawn.

That’s an appealing image, and this story about escaping attackers by taking the appearance of deer is also found in a 7th century life of St. Patrick. But it’s unlikely that the prayer, in the form we have it, goes back to Patrick’s time. Scholars say that the language and meter belong to a later period, perhaps the late 9th century. Still, it’s possible that a prayer from St. Patrick’s time was updated a few centuries later, and rendered in contemporary language. If that was the case, it would tell us in turn something about the prayer’s popularity. For a prayer to receive that kind of attention, it was likely still in frequent use, and beloved. The prayer’s emphasis on the Trinity certainly echoes the themes of St. Patrick’s preaching. After the prayer’s conclusion there comes another addition, a few lines of Latin that recall the last verse of Psalm 3, “Salvation is of the Lord.”

The Irish title of this work is Faeth Fiada, or “The Deer’s Cry.” It’s also known as St. Patrick’s “Breastplate” or “Lorica.” A lorica was that bit of Roman armor that protected the upper torso, and the term reminds us of St. Paul’s exhortations to “Put on the breastplate of faith and love” (1 Thess 5:8) and “Put on the breastplate of righteousness” (Eph 6:14).

This isn’t the only Irish Christian “breastplate” or lorica; similar prayers are attributed to St. Columba (521-597), St. Brendan (484-577), and other saints and men. Some loricae have come down to us without the name of any author, such as the one behind the beautiful hymn, “Be Thou My Vision.”

What makes a prayer a lorica? Its distinctive characteristic is that it takes the form of a series of self-protective assertions. St. Patrick’s Lorica begins:

Today I gird myself

with a mighty power:

invocation of the Trinity,

belief in the Threeness,

affirmation of the Oneness,

in the Creator’s Presence.

In subsequent verses the prayer claims the protection of saints and angels, just as our liturgical prayers do; but then it goes further, laying claim to the protecting powers of the sun and moon, fire, lightning, and other elements of Creation. As Christ commands all Creation (“What sort of man is this, that even winds and sea obey him?” Mat 8:27), we clothe ourselves in every aspect of his power. We claim that protection systematically, pronouncing it on every side: “Christ within me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me, Christ to my right, Christ to my left…” This prayer places the one saying it at the center of all power in heaven and on earth.

This isn’t like most prayers we know—and there’s something invigorating about the difference. It seems somehow alive, vibrant with power; it expresses a faith that doesn’t merely hope for, but firmly expects, God’s protection. It demonstrates utter confidence that it will receive all it says.

When I started off by saying that this prayer “charms” its readers, I was making a weak pun. (Sorry.) You might not have noticed it, but if this is a prayer, it’s not addressed to anybody. It lays claim to God’s protection, but it doesn’t speak to God. As a matter of fact, it doesn’t ask for anything. It just makes a series of announcements or proclamations, as if speaking the words was enough to unleash their power.

Such an expectation is characteristic of pre-literate cultures. In worlds where every word is a spoken word, a word has intrinsic power. Names don’t merely identify; they summon. When the bible (or an ancient prayer) notes that something is said “in a loud voice,” it means that it is said for all to hear, said publicly, “out loud.” (“Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit and she exclaimed with a loud cry, ‘Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb!’”, Luke 1:41-42.) When we speak words aloud, what we say is confirmed and enacted.

This, then, is a “charming” prayer in the sense that it resembles a charm or an incantation. Similar incantations were common in the British Isles long before the time of Christ, and some of the ancient loricae may have been pagan prayers, rewritten for Christian use. That’s not an inherently dangerous or heretical thing to do. As St. Justin the Martyr wrote, wherever truth is found we may claim it for our own use, for all truth is Christ’s. “Whatever things were rightly said, among all people, are the property of us Christians,” he said (Second Apology 13).

Nor is it wholly unusual that this prayer that doesn’t make any requests. In the Scriptures, the saints sometimes manifest spiritual power without asking for the Lord’s aid. Spirits are cast out when they told to be gone, and people are healed by contact with items that St. Paul or St. Peter have touched. We do something similar when we sprinkle holy water in places where the presence of God is needed.

This trust is also evident in the way we use the sign of the Cross, for we understand the action to be effective even if we make no accompanying request. “Let the Cross, as our seal, be boldly made with our fingers upon our brow and on all occasions,” said St. Cyril of Jerusalem (ad 313–386), “over the bread we eat, over the cups we drink, in our comings and in our goings, before sleep, on lying down and rising up, when we are on the way and when we are still” Catechetical Lectures 13.36). The sign of the Cross has its own power, even when not accompanied by a verbal request.

In fact, the question may be why we don’t use lorica-style prayers any more. Do we not feel as much of a need for thorough, all-around protection? It’s true that we live in a very safe world, compared to that of our ancestors. We take it for granted that the things we touch or consume during the course of the day will not harm us, thanks to the legal regulations (and public-image anxieties) borne by manufacturers. We expect our kids to be safe on a roller coaster, expect our homes’ wiring not to catch fire, expect that the milk we buy is really milk. Nor do we fear disease and injury as much as people did in earlier generations. We were blessed to be born into an age of medicine with drugs and techniques that render many otherwise-deadly threats harmless. (Just think about antibiotics—and anesthesia!) At the time of the American Revolution, the average age at death was only 28; not because people were old and worn out at that age, but due to the terrible loss of life among young people and children. The greatest threat was illness and disease caused by poor sanitation. As humble as it is, indoor plumbing has literally been a lifesaver.

So we feel generally safe as we go through the day, but when you consider the words of this lorica, it clearly came from a time when there was no end to potential dangers. “[P]rotect me, against everyone who will wish me ill…against the encirclement of idolatry, against the spells of women and smiths and druids…against poison, against burning, against drowning, against wounding.”

One reason we don’t say this kind of prayer any more is that we don’t feel a need to. We don’t feel in constant danger, as our ancestors did. We can give thanks for that great blessing, but should also reflect on how this widespread security affect our thinking. It makes us, to some extent, complacent. Our ancestors were reminded many times a day of their complete dependence on God. We don’t share their sense of constant danger and constant need. And that probably has an effect on our prayer life.

Our Lord said that it is “hard for a rich person to enter the kingdom of God” (Luke 18:25), and we are all rich compared to our ancestors. We enjoy comfort, health, and material delights that even kings and emperors of ancient times could not acquire. We take for granted homes with central heating, means of travel that are speedy and safe, and food stores ever-refilled with goods from all around the world. We enjoy a high degree of safety and comfort, and as far as we can see, God doesn’t give it to us; we secure it for ourselves.

Such conditions may lead us to take God for granted—or worse. In recent decades of there has been a trend of presenting Christian faith to potential believers as something that will please them and meet their “felt needs.” This turns the concept of salvation upside-down; it’s as if we are self-sufficient, but God needs our patronage. We will allow him to try to please us, though we don’t feel any need for him.

But God is not as dedicated to making people happy as a neighborhood café might be. As a consumer product he’s notoriously unreliable. His “customers” may conclude that, while humans handle their responsibilities reliably (for example, getting safe milk to the supermarket), God regularly makes a mess of the things he’s supposed to do (preventing hurricanes and disasters). Modern-day “customers” are unaware of any need for repentance; that topic is hushed up, because talk of repentance scares buyers away. So they can come to see God as an incompetent employee, and fire him.

Yet all this confident self-reliance is less warranted than it seems. Disaster could be only a step away—a fall on an icy sidewalk, bad news from a doctor. And, sad to say, for some people that’s what it’s going to take. Some people who won’t take God seriously until he’s the last thing they have left.

Surely the goal is to live with whole-hearted reliance on God, without needing the spur of suffering. A contemporary elder (and I wish I remember who) said that, though people think that unceasing prayer is very difficult to do, it’s actually quite easy. It doesn’t even take practice. Anyone might start praying right now, and continue with fervor until life ends. All it takes is catastrophe.

Let’s use this “Breastplate,” then, to remind ourselves not only of God’s infinite power, but of our own powerlessness. Let’s use it as a reminder that we need him much more than we think.

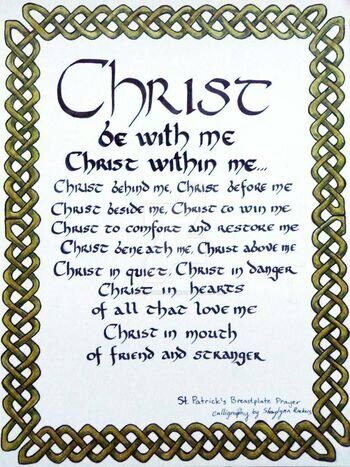

How might we use it? The repeated line, “Today I gird myself,” lets us know this was a morning prayer (other translations render it, “I rise today” or “I bind to myself today”). The ancient usage, it seems, was to recite these words every morning, and if we made that a habit it would soon lodge in memory. We might want to commit the passage “Christ be with me, Christ before me” to memory more deliberately, as it’s a prayer that would be handy in many situations. Few prayers concentrate so well or so simply the reality Christ’s presence.

The preface to the Breastplate states that it should be said “with [the] mind fixed wholly on God,” so this is not a magical formula but a declaration of faith. The Nicene Creed is another such statement of faith; in worship, we stand in God’s presence and declare what we believe. When we say St. Patrick’s Lorica, we stand in God’s presence and declare ourselves his children, protected by his power. Our ancestors spoke this prayer in times far more harrowing than our own, and knew the God on whom they called. We, junior brothers and sisters in faith, can participate in this prayer and, by God’s grace, begin to glimpse the glory that they saw.

Faeth Fiada: ‘Patrick’s Breastplate’

[Translation by John Carey, King of Mysteries: Early Irish Religious Writing (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2000), 130-135. Permission given to reprint by the author and Four Courts Press.]

Patrick made this hymn; it was composed in the time of Loegair son of Niaqll. It was composed in order to protect him and his monks from deadly enemies, who were ly8ing in wait for the clerics. And it is a breastplate of faith, to protect body and soul against demons and men and vices. If anyone recites it every day, with his mind fixed wholly upon God, demons will not stand against him, it will protect him against every poiseon and jealousy, it will guard him against sudden death, it will be a breastplate for his soul after death. Patrick recited it when Loegaire had set an ambush for him, lest he come to Tara to spread the Faith, so that it seemed to those who lay in wait that they were wild deer, with a fawn following them (that was Benen). And its name is Faid Fiada (‘the Deer’s Cry’).

Today I gird myself

with a mighty power:

invocation of the Trinity,

belief in the Threeness,

affirmation of the Oneness,

in the Creator’s Presence.

Today I gird myself

with the power of Christ’s birth together with his baptism,

with the power of his crucifixion together with his burial,

with the power of his resurrection together with his ascension,

with the power of his descent to pronounce the judgment of Doomsday.

Today I gird myself

with the power of the order of the cherubim,

with the obedience of angels,

with the ministry of the archangels,

with the expectation of resurrection

for the sake of a reward,

with the prayers of patriarchs,

with the predictions of prophets,

with the precepts of apostles,

with the faith of confessors,

with the innocence of holy virgins,

with the deeds of righteous men.

Today I gird myself

with the strength of heaven,

light of the sun,

brightness of the moon,

brilliance of fire,

speed of lightning,

swiftness of wind,

depth of sea,

firmness of earth,

stability of rock.

Today I gird myself

with the strength of God to direct me.

The might of God to exalt me,

the mind of God to lead me,

the eye of God to watch over me,

the ear of God to hear me,

the word of God to speak to me,

the hand of God to defend me,

the path of God to go before me,

the shield of God to guard me,

the help of God to protect me,

against the snares of demons,

against the temptations of vices,

against the tendencies of nature,

against everyone who will wish me ill,

far and near,

among few and among many.

Today I interpose all these powers between myself

and every harsh and pitiless power which may come against my body and my soul,

against the predictions of false prophets,

against the black laws of paganism,

against the crooked laws of heretics,

against the encirclement of idolatry,

against the spells of women and smiths and druids,

against every knowledge which harms a man’s body and soul.

May Christ protect me today

against poison, against burning, against drowning, against wounding,

that many rewards may come to me.

May Christ be with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me,

Christ within me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me,

Christ to my right, Christ to my left,

Christ where I lie down, Christ where I sit, Christ where I stand,

Christ in the heart of everyone who thinks of me,

Christ in the mouth of everyone who speaks to me,

Christ in every eye which looks on me,

Christ in every ear which hears me.

Today I gird myself

with a mighty power:

invocation of the Trinity,

belief in the Threeness,

proclamation of the Oneness,

in the Creator’s presence.

Salvation is of the Lord,

salvation is of the Lord,

salvation is of Christ;

may your salvation, Lord, be always with us.

When first becoming aware of this prayer, as an adult, it was quite comforting visualizing Christ spiritual breastplate. Who, I believe is most in need, are today's children. With foster children at record numbers, if nothing else the children can be introduced to a couple verses and have a thought or prayer to remind of a friend in Christ. Of course the guardians in their life, many parents do not know how to protect anymore, what was an instinct, is apparently fading. This prayer lays out how timeless the ways, environment can harm.

A couple years ago bluebirds made their nest in my backyard laundry pole. As I observed, the male bird, especially, bomb-dived other birds & squirrels as they fled away from the nest. The male & female bluebirds had a system most diligent & impressive. Maybe by introducing, just a snippet of St Patrick's "Faid Fiada", it can be a meaningful thought,prayer, through the day. Observing nature, reminds us a guardians place is urgent, the universal role of providing a safe path, treasuring new life,play in the sun, & strengthen to thrive.

As the medical crew & victims in this COVID- 19 threat, yes, a reminder we are powerless, we cannot do this alone: May Christ protect me,….May Christ be with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me, Christ within me…

Thank you for sharing St Patrick's faith & prayer to get through our day!

This has been a very enlightening blog. I’ve never read the whole prayer before, only praying the Christ before me Christ behind me part and as a prison chaplain the whole prayer speaks volumes to me with regards to my own work amongst prisoners but also a prayer I want to introduce to prisoners whose faith is there but needs encouraging. Thank you once again.

your blog is amazing